There Is Only One Level In Like A Dragon

This post can also be found on my Linkedin here!

Excellent level design isn’t always about variety, choice, or an expansive environment. In an industry where the size of a game’s play area is often one of its greatest selling points, I think it’s worthwhile to look to places where the opposite is true.

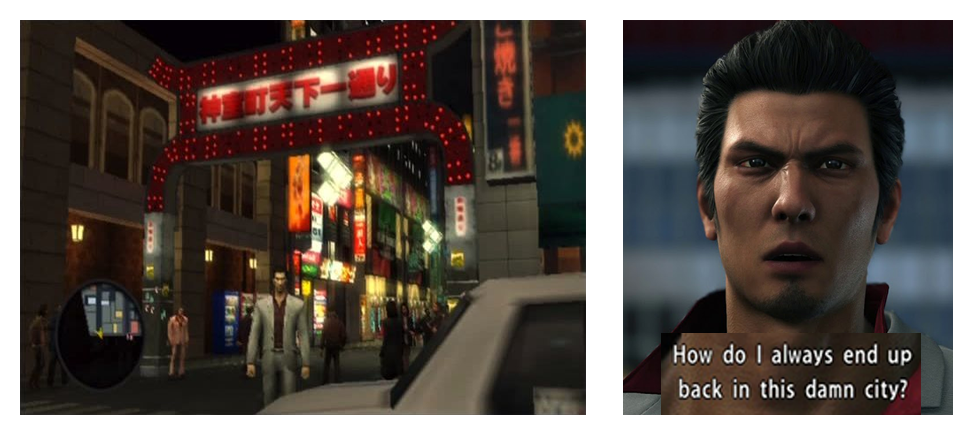

Since 2005, Kazuma Kiryu has called Kamurocho his home. 18 games in the Like A Dragon franchise are at least partially set in this fictional district of Shinjuku. But how does remaining in one place for over 20 years still manage to stay fresh? Like A Dragon is a series about clinging to the past in a world that has moved beyond you, a theme that it masters by balancing the comfort of familiarity with the ever-marching evolution of a living, breathing city.

Urban Density

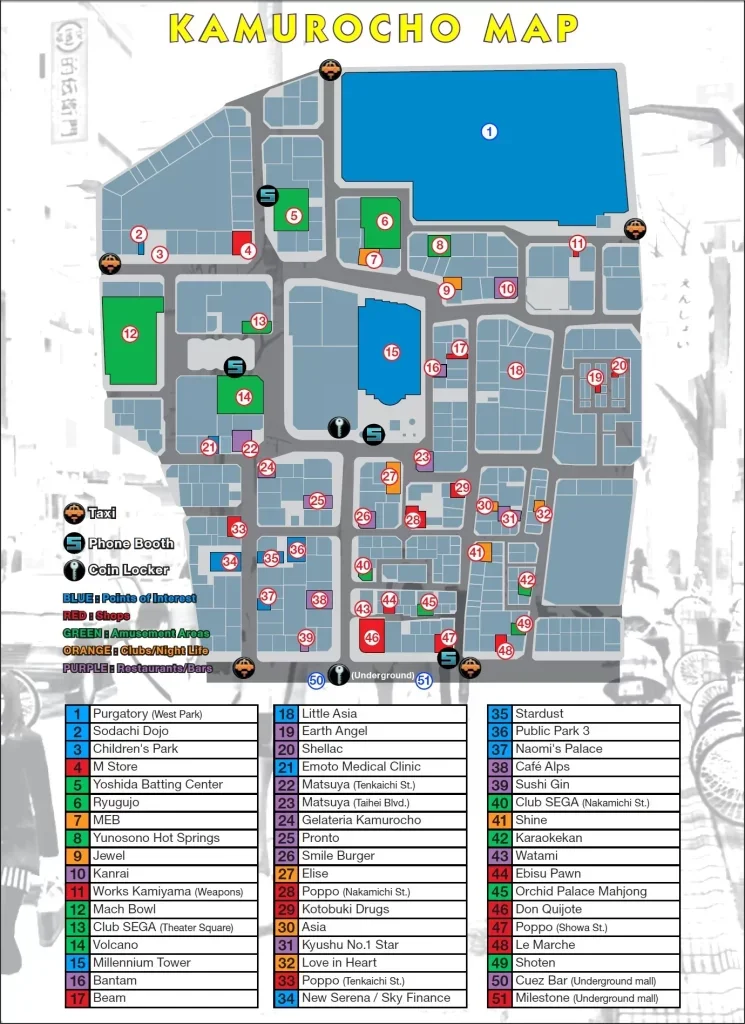

The first and foremost strength of Like a Dragon’s world has always been the sheer amount of things to do in Kamurocho. Between bare-knuckle brawls with gangsters, you’ll eat at restaurants, entertain yourself with attractions, and assist the city’s biggest weirdos with their troubles. As you explore the city, you will naturally familiarize yourself with it much like you would your actual neighborhood. This comfort builds a powerful foundation for the player, forming a bond between them and the city. But densely-packed content is not the true strength of Kamurocho’s design. It’s what can be done with it as the years go by, when that familiarity you’ve built is challenged.

A Change In Perspective

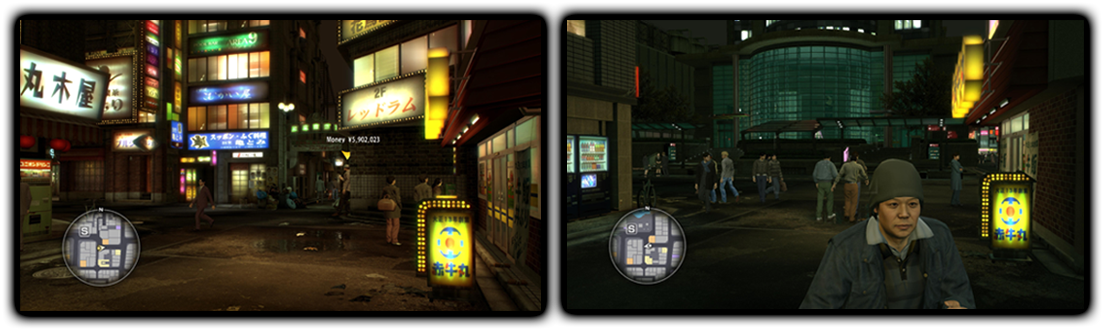

Kamurocho’s main method of evolution is not through visible change, but altering the player’s view itself. As the stories unfold, the player is introduced to characters who all see the city differently, and engage with the same locations in different ways. For example, the iconic Tenkaichi Street is a place of safety for Kiryu, or a source of busywork for Akiyama. The escaped convict Saejima is all but forced to avoid the streets entirely, using the city’s many alleys to evade patrolling cops. A simple change in the player’s point of view can shift their entire experience, making the same environment into something completely new. Kamurocho isn’t totally opposed to making major changes, however…

The Passage Of Time

Like A Dragon’s strong emphasis on story often bleeds into the city itself, making dramatic changes as the years pass. Businesses come and go, entire city blocks are remodeled, and backstreets become skyscrapers. Changes like these are used as symbols of the world slipping past the characters, but they also serve a powerful gameplay purpose: they shift the player’s relationship with the world in a profound, tangible way. The impact of these alterations can vary, of course. Removing a beloved location can be scary, but opening up previously blocked areas could promote curiosity as well. After all, one of Like A Dragon’s greatest morals is to keep moving forward. Understanding and Embracing the power of change is just as important for game devs as it is for gangsters.

The essence of every picture is the frame. By understanding the power of familiarity and limitation, developers can create games that leave a greater impact on their players. Like A Dragon leans hard into its setting, using just a few blocks of Tokyo to illustrate its themes, cultivate attachment in the player, and introduce gameplay variety without designing new levels.

This isn’t to say all games should eschew larger worlds or numerous unique levels. Instead, Kamurocho proves that perspective is key to strong level design, and that player familiarity can create unique experiences when challenged by change and evolution. If you foster the bond between the player and the level and offer new ways to view the world they’ve grown close to, they’ll be perfectly fine even with only one level.